I should probably preface what you’re about to read by saying that I don’t just play Minecraft when I’m depressed or anxious. Broadly speaking, I tend to play it because it’s fun. That’s what video games are for, right?

To anyone that sees me pop up on their friends list playing it on the reg: please don’t worry. Sometimes it’s just nice to dip into Minecraft every now and then. With that said, I’ve lost count of the number of times where Minecraft has come to be a playful form of escapism in the days, weeks and (occasionally) months mired by low mood and anxiety.

Sometimes facing the real world feels like it’s a bit too much. The idea that video games provide an ideal escape is nothing new, of course, but in the 14 years since its release, I’ve yet to find a gaming outlet quite as comforting, if not downright all-consuming, as the creative joys offered by Minecraft.

Feeling low? Build something stupid. Feeling anxious? Build something stupid. Feeling like you can’t really face interacting with people in real life? Build something stupid whilst chatting to someone who is building something even more stupid than whatever you’re building. That’s how I dealt with my mental health struggles in the days before I sought any sort of professional advice.

One of Minecraft’s greatest strengths has always been its flexibility. There’s a ‘story’ of sorts to follow, but that’s not obligatory. Even if you’re just setting out to build, enemy mobs can be switched off to keep things laid back. There’s only so many times you can watch a Creeper destroy something you’ve spent hours digging resources for. Inevitably, Peaceful Mode gets activated pretty quickly.

I’ve been dabbling in gaming forums since the mid-00s, and over the years I’ve amassed a group of pals who were, despite all better judgement, just as excited by the idea of building giant structures in a pixel environment as I was 11 years ago. Minecraft arrived at a time where FPS fatigue was setting in, so the idea of playing something that didn’t result in us all screaming at each other was appealing.

Hundreds of hours later (and without the benefit of Creative Mode, which would come later), we’d mined countless resources, carved out underground caverns and built various absurdist creations that existed solely to make each other laugh. There was giant pixel art of Danny Dyer’s face and a giant sphynx with our friend Chris’s face on it. There was skywriting featuring obtuse references to TV ads of the late 80s that I’m too young to remember.

A month after Minecraft launched on the Xbox 360, I lost a relative for the first time. I was in a bad way and didn’t really know how to process things. I worked through a lot of it by chatting to friends online, many of whom I’d only met once or twice in real life - often whilst building a giant underground pyramid, or an effigy of beleaguered singer Mark Morrison, or something. I wasn’t running from grief. I was just dealing with it in the way that felt appropriate at the time. And it helped. A lot.

In late 2021, the game took on a different purpose for us entirely.

When we started gaming online in 2006, our friend Mark was always there. Every week we’d get together and play games into the early hours. When Minecraft arrived on the Xbox 360 in May 2012, we’d spend hours trying to catch each other out with indulgent, self-referential builds. Mark was often one of the people we built stuff to get a reaction from. He was baffled and overjoyed in equal measure.

Online communities ebb and flow and ours was no different. Over the next decade some of us would stay in regular contact, while we lost touch with others entirely. Mark went on to start a family and do his own thing, but he always made a point of checking in with us on social media from time to time. He had his own life, but he knew where we were and it was always nice to see him pop up online.

In September 2021, Mark passed away suddenly. We found out via Twitter, of all places. We’d never lost one of our own before. I’d never even lost a friend before. Considering we’d only met in person a handful of times over the years, I didn’t really think it would affect me as much as it did. But this was someone who, for many years, I’d spoken to for hours, week in, week out. We were devastated.

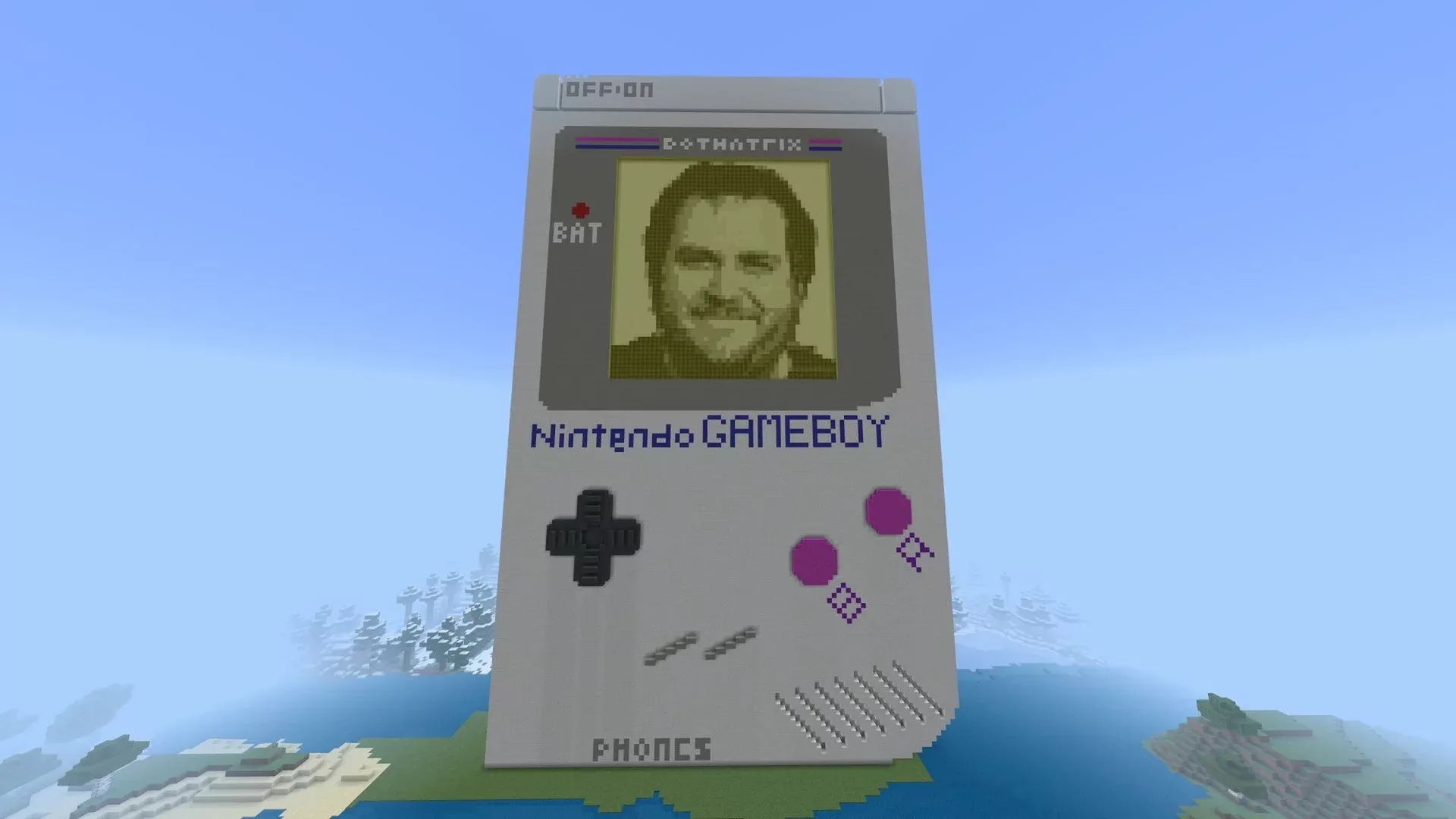

The coping mechanism was a no-brainer. We took to Minecraft, dusting off the old map we’d used to make our creations back in the day. Porting it to a server, we set to work, revisiting the classic designs and ultimately deciding to build a tribute to Mark. The end result was an enormous pixel art rendition of Mark’s face, rendered in a cathode-ray monstrosity TV. We even built him a giant ZX Spectrum.

There was certainly an aspect to this where we were doing it because it was stupid. Mark would have loved that. We’d probably still have done something like this for him if he was still with us. But the fact that he wasn’t made it all the more poignant. And in some small, ridiculous way, honouring his memory in this way provided some comfort.

For all the talk of toxicity in gaming, there are countless stories like ours. Games might not be able to fix our problems, but their potential for healing can’t be understated. The saying goes that a problem shared is a problem halved. In my experience that’s always been true. Doing so whilst building a monolithic, pixel-accurate GameBoy with one of our faces on it will always be my personal preference though.

If you are affected by any of the issues raised in this Insights piece, please check out the Safe In Our World signposting page.